Written by: Shreya Seth

Kolkata, India

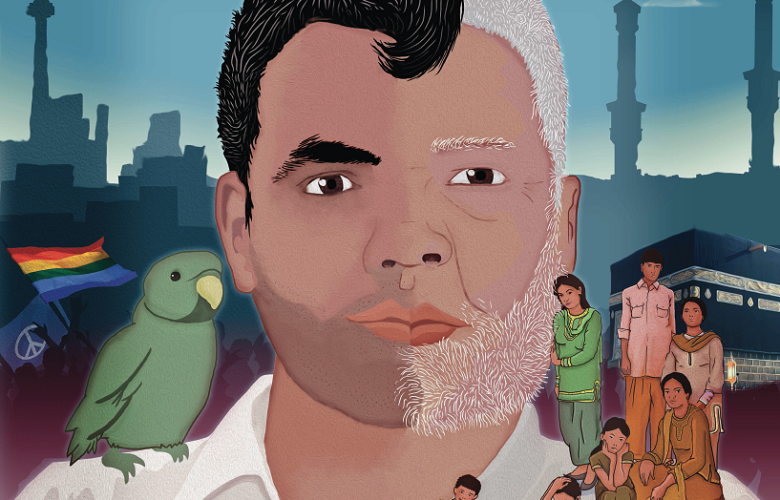

Film Review: Abu

Country: Canada-Pakistan

Director:Arshad Khan

The camera is a beautiful device that succinctly captures and retains all that our restless vision and cramped memories cannot. However, it might seem to be losing its charm in a world that is predominantly obsessed with capturing everyday life, not with the intention to retain or revisit, perhaps to abide to a false sense of self- portrayal and self-validation. Amidst these changes, Arshad Khan’s documentary ‘Abu’ comes as a refreshing take on personal life told primarily through a camera that is not a mere intruder or an object that prompts one to alter their expressions or mannerisms, but one that captures an individual with all their idiosyncrasies, devoid of any distortion.

The Pakistani-Canadian filmmaker takes us through his journey of self-discovery and acceptance, family dysfunction and negotiation, and the cross-cutting identities that define him as he amalgamates archival footage, animation, and snippets from Bollywood films and songs to narrate his deeply personal story, set against a wider political context. His documentary, titled ‘Abu’, (meaning father) traces the life of his father who migrated from India to Pakistan in the aftermath of the Indo-Pak Partition in 1947 and eventually joined the Pakistani army, before marrying his mother, Arjumand Bano. Arshad Khan, recounts his days in Islamabad, a then progressive city in his opinion, as soothing yet troubling. The voice-over is subtle and moving as Arshad recollects instances of sexual abuse and the inability to confide in his family, his sister Asma, the unapologetic artist who he admired and loved, and the setbacks his father faced when his business ceased to flourish.

While Pakistan was witnessing major political changes under the dictatorship of Zia-ul-Haq, who was later overthrown by Benazir Bhutto, Arshad was witnessing a storm within as he tried coming to terms with his own sexuality. Fourteen year old Arshad who fell in love with a classmate, Elvis, felt that ‘being gay in Pakistan was tantamount to being a paedophile or a rapist.’ Before he could overcome the fallout of his relationship with Elvis, Arshad’s father decided to migrate to Mississauga, a suburb in Toronto, Canada. The intersection of his multiple identities- a Pakistani-Muslim who was gay, played out at its worst during High school as he tried to fit into a city and culture that outrightly rejected him as deviant and a father who kept growing intolerant and orthodox in an alien country. It was later in his University years that Arshad distanced himself from his family who were vigorously marching towards religious conservatism, while he found solace in carving a distinctive identity for himself.

The documentary ‘Abu’, a visual memoir, is rich in content with photographs and audio-visual clips owing to the VHS camera owned by his father, which communicate an insider’s perspective to his family and relationships with considerable ease. Moments from picnics, birthday parties, trips, weddings, and discussions that are inherently intimate in nature, flow in tandem with the placid voice-over as Arshad narrates his story. The director tries to arrive at the unfathomable relationship with his father through the camera- an object that captures their starkly different personalities, but also brings them closer. Clippings from his father’s VHS camera and later the smartphone he bought to capture things around him are used in a subdued fashion to comment on Arshad’s inability to communicate with his father, or his unwillingness to understand for that matter. ‘Abu bought a smartphone and captured everything vertically despite my insistence that horizontal would give him a wider view of the world.’ In the process, he also ends up exploring more of the nuanced relationship with his mother who was quick to adapt to changes around her, but refused to accept her son’s identity, which repeatedly finds expression in Arshad’s unspoken agony. At no point, though, does the documentary in its intensely personal approach seem to alienate the viewers, instead the connection keeps growing stronger with every passing frame.

The eighty minute documentary is not just a layered confession, it is about everything ranging from everyday homophobia, racism, conservatism, suppression, self-loathing, love, and indignation that Arshad encounters on the path to self-discovery, acceptance, and assertion. The camera’s unquestionable presence is the only constant in this journey.