Written by: Shreya Seth

Kolkata, India

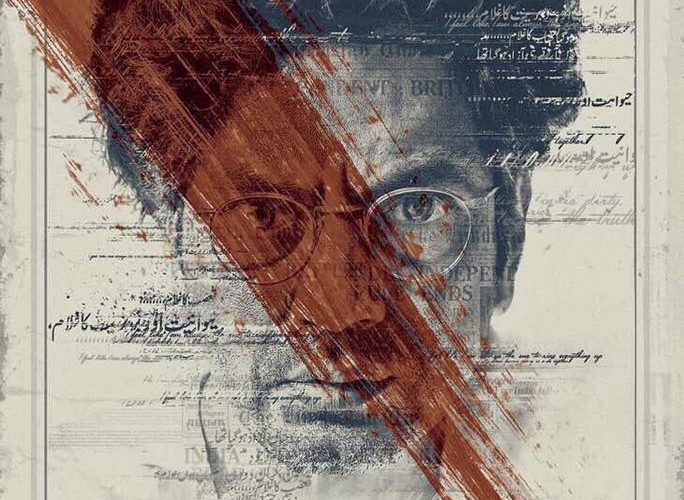

Film Review: Manto

Director: Nandita Das

Cast: Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Rasika Dugal, Rajshri Deshpande, Tahir Raj Bhasin, Rishi Kapoor, Paresh Rawal, Bhanu Uday, Vinod Nagpal

A growing climate of intolerance has no room for dissent. Saadat Hasan Manto, an Urdu author and playwright born in British India, met the same fate that many others do for speaking their minds today. Infamous for his raw portrayal of reality, Manto wrote extensively during the partition era of the 40’s and was tried for obscenity in British India and later in Pakistan.

Written and directed by Nandita Das, the film ‘Manto’ is a biographical account of the author’s life, set in the backdrop of the chaotic Indo-Pak partition era of the late 1940’s where many lives were uprooted, while others perished. The narrative chronicles Manto’s personal life and his short stories, interwoven so effortlessly into the fabric of the film that the characters in his stories come across as more authentic than those in his surroundings. The director portrays Manto (beautifully essayed by Nawazuddin Siddiqui) as a disgruntled, unapologetic, and self-destructive writer who fails to reason with a world that often misconstrues his writings as sexually explicit. “If you cannot bear my stories, it is because we live in unbearable times.”

The first half of the film traces his life in the city of Bombay, his struggles as a writer, and the amorphous relationship with his contemporaries. Amidst the many people who are indispensable to this narrative such as his friend Shyam (Tahir Raj Bhasin) and actor Ashok Kumar (Bhanu Uday), are two women- his wife Safia Manto (Rasika Dugal) and writer Ismat Chugtai (Rajshri Deshpande). Safia is compassionate and gentle, unwavering in her support even when she suffers silently. Ismat, on the other hand, is bold and rebellious. While the director succinctly captures his subtle exchanges with these women, it could have been delved into a little further to reveal the inherent contradictions of his persona- the strong and nuanced female characters in his stories juxtaposed with those around him. A scene in the film which captures a brief exchange between a film producer and the author also depicts an instance of harassment, but Manto prefers to look on, leading one to believe that his response is impressionistic and would navigate its way through his writings.

The film evokes the aftermath of the Partition and the communal hatred that engulfs the Indian subcontinent, with Manto’s growing insecurities slowly taking over his reluctance to leave the city. Events in the film unfold at a steady pace until Manto’s decision to leave Bombay and move to Lahore which has been hurriedly portrayed, perhaps to underplay the tragedy. Kartik Vijay’s cinematography coupled with Rita Ghosh’s production design help recreate the vintage charm of coffee houses and railway stations, and the disorder that marks the pre-independence and the post-independence era.

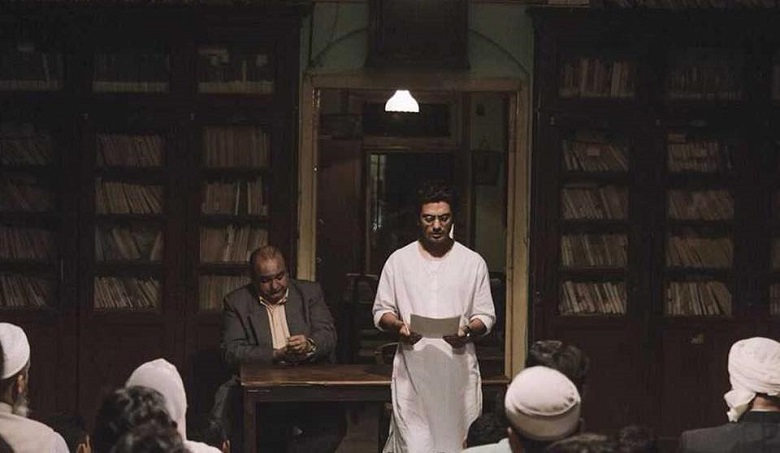

The biopic progresses as it depicts the constant hardships of a non-conformist who is heavily critiqued for his literary works and eventually fails to support his family. He is afraid of being jailed yet remains uncompromising in his demeanour. Das’s genius lies in her ability to effectively use Manto’s original writings as dialogues in the film written in a mix of both Urdu and Hindi to express his anguish and the nonchalance of those around him. “When we were enslaved, we dreamt of freedom. Now that we are free, what should we dream of?”

Manto is brutally honest and often dismissive of those who refuse to treat his works as anything but the bleak reality. However, he is taken aback when his dear friend Faiz Ahmed Faiz appears in his defence during a trial and claims that while his story ‘Thanda Gosht’ is not obscene, it cannot be regarded as ‘the highest form of literature’. His relationship with Faiz amid many others, remains potentially unexplored in the film, augmenting the gap between the viewers and the narrative.

Manto’s writings are part of a wider theme and commentary on the destructive nature of the divide and the plight of women who had been at the receiving end of the barbarity. The lines between fact and fiction are blurred in Das’s biopic as she tries to fuse his literary works and present them as an extension of his reality. The film, however, falls flat in its attempt to gauge the downfall of the author who eventually succumbs to alcoholism and overlooks the complex workings of his mind, instead focusing on the mundane nature of tragedy. The scenes of the courtroom proceedings and the numerous cameos are rushed and remain scattered, leaving little or no space to establish their presence in the broader narrative.

Das’s biopic is crisp and devoid of any melodrama, but the movie largely draws and relies on the author’s literary masterpieces, especially the spine-chilling tales of ‘Khol do’, that depicts the violence and rape of women during the partition era, ‘Thanda Gosht’ which encapsulates the theme of necrophilia, and ‘Toba Tek Singh’, an unforgettable account of a lunatic inmate in Lahore’s Mental Asylum (remarkably essayed by Vinod Nagpal) who wants to locate his hometown Toba Tek Singh but doesn’t know which side of the border would lead him there and breathes his last as he falls between the two borders.

Despite the inconsistencies, the biopic manages to leave a bitter aftertaste as the story of a man who refused to be silenced.