Written by: Pema Bhadra

Guwahati, India

Photo: Indian Navy, ChildAid Network

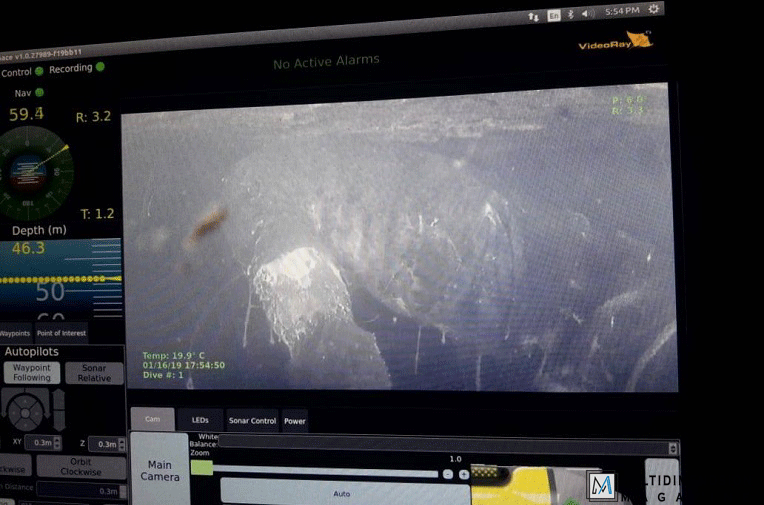

36 days passed. On 16 January 2019, after a joint operation of the Indian Navy and NDRF, it was confirmed that Indian Navy ROV had detected a body 160 feet deep inside the main shaft. The body has been pulled up to the mouth of the rat-hole mine and will be brought out of the mine under the supervision of the doctors.

Living Dangerously

According to the study done by Impulse NGO, over 10,000 people are estimated to have died in rat-holes between 2007 and 2014 in Meghalaya. Impulse’s study also estimates that there are 70,000 child labourers in the area. Another Tokyo based international human rights NGO Human Rights Now (HRN) suspects the number might be higher.

Impulse study shows: the working conditions at the mines are extremely hazardous. The ladders that labourers climb in order to enter the mines are incredibly dangerous, especially during monsoon. As rat-holes are only about 2 feet in height, mine managers prefer to send the children deep into those holes to extract coal. There are little oxygen and insufficient ventilation in the deep, narrow holes.

HRN report says, “There is a total lack of safety measures to prevent accidents, which occur frequently and are often fatal. No equipment, apart from headlamps, is provided to protect labourers from accidents. Flooding also occurs; existing tunnels fill with water and are sometimes dug into by labourers constructing a new hole, causing the water to flood through and drown them. Although accidents often cause deaths and injuries, incidents are not reported to the police. Mine managers do not record labourers address or family details. So when a labourer dies, families are often not informed of their loss. Unclaimed bodies are cremated and buried around the mines. The deaths of missing children go unreported.”

Impulse study revealed that out of the 80% child labourers a large majority (77.6%) were from Assam. Surprisingly, only 6.2% were from Meghalaya. 28% of the respondents said that they were from Karimganj District in Assam, but it could not be conclusively determined whether they were indeed from Karimganj or had come from Bangladesh across the porous borders. Other states of origin include West Bengal, Tripura, Bihar, Manipur, and Nagaland, all of which are geographically close to Meghalaya. Managers definitely have to pay less for these child labourers.

A number of children had started working at the young age of 4 years. The data also revealed that 43.5% of the children had started working at the age of 14 years or even earlier. The levels of noise, heat, chemicals, and toxins present in the coal mines are dangerous to children. Children are more prone to accidents than adults. 90% of the interviewed community, working underground in the mines, reported that they were initially very afraid to go into the dark and suffocating rat-holes, but gradually got used to it.

A very important section of the study done by activist Haisna Kharbhih’s team pointed out, 96.9% of the child labourers were either working full-time or even if they were working part-time, they were completely excluded from the process of formal education. 92.6% of the children cited poverty as the reason for dropping out of school. 63.7% of the children replied that if given a choice they would rather work than go to school. Even at a young age, most of the children seemed to have an overwhelming sense of responsibility toward their families.

Light at the end of the Tunnel

In the villages of Coal belt, people don’t send their children to schools. They send them to work in the coal mines instead. But they are not realizing that they are infringing upon the rights of children. One of the most important rights is, right to education. People here are all dependent on the money they get from coals. But the deposit of coal is gradually reducing and after the NGT ban, people must start searching for alternatives, which is impossible without education.

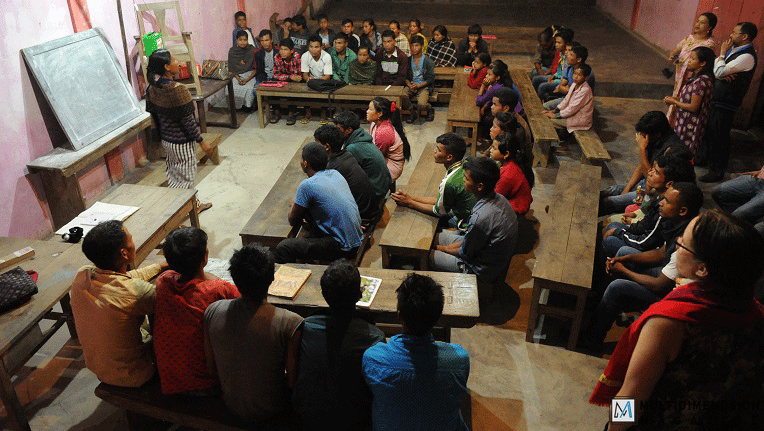

Childaid Network, a charitable foundation for children in need, based in Germany, joined hands with Bosco Integrated Development Society and started their intervention in Khliehriat coal mines in 2014. Fr. Cyril Tirkey, from Bosco Integrated Development Society said, “We started with a health project, then a community project in 2014, the year NGT Banned the mining activities. Then we started a school with the help of the village. First, we created awareness among them and formed a village education committee. We told them, if they can’t go to morning schools, they can attend night schools that are separately designed for the children. If the children are not educated, they won’t survive in the coming years.”

Filed Co-ordinator Jubilancy Dkhar informed that children have been grouped in A, B, C according to grades. The children are mostly from the age group of 15 to 20 years. In the daytime, these children go to work and in the evening they come to school. But sometimes the schools don’t open as the children don’t come. After coming back from a day long, tedious mining job, they are exhausted.

So the team started home visits with local facilitators to make them understand that after the deposit of coal exhausts, the next generation can only survive with the help of education. Jubilancy says, “We had to convince the village headmen and the leaders. Their experience was thought-provoking for us and we started re-thinking our strategies. Apart from regular night school, we came up with an idea of Children’s Club. The local children have a meeting there and try to relate to the social issues around them.” Field Supervisor Mechanki Dkhar says, “Children’s Club is helping the children to improve not just in studying but also in their talents like singing, dancing, drawing etc.”

According to Dr Martin Kasper, founder of the ChildAid Network, “The goal is that these children eventually learn about the importance of education and send their own children to schools. In 2014, we started with 14 schools. Presently we have about 50 such community schools in the area – mostly around Khlierhiyat. The main aim is to see the children happy at the end of the day.”

Information and reference credit: ChildAid Network, Bosco Integrated Development Society, Impulse, Human Rights Now, East Jaintia Hills district administration.