Written by : Anuja Dutta

There’s a new spectre in town. And it’s here to crack you up.

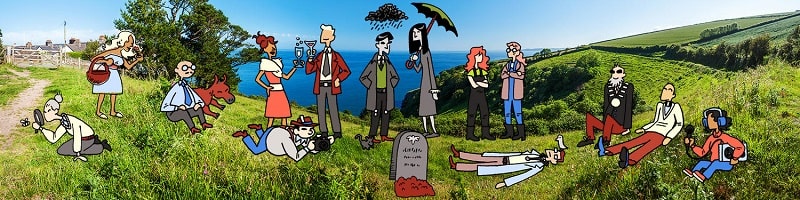

‘Rudyard Funn runs a funeral home in the village of Piffling Vale. It used to be the only one. It isn’t anymore.’

Death has a way of triggering within us a sense of discomfort one can sometimes associate with old and extremely embarrassing childhood memories: we know them to be true yet can’t ever seem to come to terms with the full thrust of its meaning and aftermath. In many ways, we learn to survive (and not embrace) the event of death the same way we survive childhoods: with a hint of submission. However, director/producer Andy Goddard and John Wakefield’s morbidly marvellous podcast ‘Wooden Overcoats’ – an anguishedly comic commentary on death and its compatriots in the fictional village of Piffling Vale – doesn’t submit too easily to the finality of death. It pokes, provokes, and perseveres despite the challenges lain bare in the narrative and nature of past lives and present.

A dysfunctional family-drama woven into the business hazards of running a funeral home – it is a tale certainly not told by an idiot but a very observant and articulate little mouse named Madeleine. It will be almost five and a half years since this British podcast sitcom aired its first episode on BBC Radio 4 and has been gathering critical acclaim as each season gets progressively darker, wilder and hilariously profound. This brainchild of head writer David K. Barnes navigates a tabooed subject through a series of wonderfully eccentric characters struggling to find their semblance of normalcy in a godforsaken town. Here’s a sneak peek of what you can expect from them:

1) Antigone Funn –

tragically named and gloriously funny local mortician of ‘Funn Funerals’ and troubled twin to her elder brother by-one-week, Rudyard. Although clinically asocial (‘the poor dear had been diagnosed with depression within twenty minutes of being born: a world record which gave her no consolation at all’) Antigone has a penchant for obscure French movies, raunchy novels, experimenting with scented embalming fluids, and a perverted, hidden crush on local rival, Eric Chapman, who threatens to drive their only family business into bankruptcy. Over the course of three seasons, the listeners realise that for all her social awkwardness and childhood insecurities, Antigone is actually quite talented, and not just in the art of embalming which requires a steady heart and confident hands.

2) Rudyard Funn –

brother to Antigone who likes to boss people around no matter how ridiculously understaffed his whole funeral enterprise is. Difficult, short-tempered, and a bit of a loner, Rudyard takes immense pride in getting ‘the body in the coffin in the ground on time’ and will leave no stone unturned to sabotage the entrepreneurial charm of his rival, Chapman, whom he never calls by his first name. Although having a loyal sidekick in his (only) assistant, Georgie, the only real friend he has is a mouse named Madeleine – the squeaky, ambitious narrator of this podcast who hopes to get her book (‘Memoirs of a Funeral House Mouse’) published one day. Although the dynamics of the brother-sister duo is premised on a mutual distaste of one another packed with witty banter, Rudyard can sometimes be surprisingly affectionate and self-reflexive, even if such daunting exercises last as long as five seconds.

3) Georgina Crusoe –

Probably the only level-headed person in Piffling Vale. Georgina and her Nana had a rather spectacular arrival on the island when one stormy night, a giant wave literally swept their row-boat onto the shores of Piffling. An aggressively efficient taskmaster of any odd job thrown at her (‘I’m great at arson’), Georgie divides her time between caring for her Nana and working a minimum-wage job as a funeral firm assistant. Fairly outgoing and confident (and a great deal more likeable than her employers), Georgina’s love and loyalty for the Funns get heightened by Chapman’s romantic interest in her despite Georgie’s growing dislike for Eric.

4) Eric Chapman –

resourceful stranger and the undertaker antagonist of Piffling’s tragicomedy. Eric is new to the place but his industrious spirit and good looks are already knocking down hearts and long-standing business monopolies in town. Ambitious and ridiculously able at any project he sets his heart on, Eric’s mysterious past lends his character a dualism which only strengthens the narrative formulae that every dashing dreamboat emerges from murky backwaters. Bringing forth ancient insecurities which voyages to new destinations in hopes of ‘starting over’ can barely hide.

Apart from this assorted set of oddballs, there are ample other characters who rescue Piffling from plummeting into an air of nonchalance and true seclusion. We have the village reverend – Nigel Wavering – an agnostic with a hearty cynicism in God (‘unless you don’t believe in that sort of thing, which I won’t hold against you. Mind you, God probably will, unless He doesn’t exist, in which case He won’t have anything to complain about, really’); Mayor Desmond Desmond known for his unflinching optimism (‘I’m sure it’s going to be fine’) despite occasional bouts of existential crisis; local purveyor of flowers, hilariously yet aptly named Petunia Bloom, renowned for her performances and risqué nature; Herbert Cough – and booth-operator of Piffling Royale Cinema famous for churning out inaccessible French films every Thursday night for its one loyal spectator, and so on and so forth.

For all its underdog status toggling between the designations of ‘village’ and ‘town’, Piffling’s municipal/territorial boundaries unmistakably bear a hint of spectral aura about it – deviating from the norms of realism as ghost stories often do, which really shouldn’t come as a surprise given that the lives and labours of Piffling residents – like those of any town aspiring to greatness – are heavily punctuated by tangible and symbolic deaths, and the tricky economic machinery of its emotion and industry. In many ways, then, Piffling Vale – tucked away deeper and further into the recesses of the English Channel – can very easily become an inverted comic ‘double’ of our own individual sites of terror and anxiety. In fact, the world of Piffling is eerily strewn with doubles: twin proprietors of a business who resemble each-other in many ways; twin funeral homes which are the atmospheric opposites of each other, possessing hugely different business principles and reputations; characters relying on strange pseudonyms to vent their deepest sexual fantasies; confectioners quite convincingly doubling as detectives because, for all its sunshine and birdsongs, Piffling can become quite vengeful. And the list goes on.

While the idea of a ‘double’ hints at a modicum of release or desired duplicity, it would be unwise to read Piffling as free from its darkness; in fact, its narrative embryo develops in a literally dark, dank place: a troubled mortician’s embalming chamber, with plot twists that would pull us deeper into the earth’s pit – again, literally – but not without its potential for redemption, or simply, redressal of past wrongs. The listeners find ample narrative insinuations to traumatic family history – subdued accounts of abuse, infidelity, alcoholism, guilt, even an occasional murder – flow as a quiet, ominous undercurrent to Piffling lives; reminding us, time and again, that certain horrors exist which, if not countered by humour and reckless laughter, can grow to swallow us whole. And it probably will. Hence, listen carefully.

While a good part of Piffling’s tragedy – and by extension, its narrators’ – lies in the fact that they find themselves painfully tied to a place which offers them very little scope or recognition for emotional or economic development, that repeated loss of self-worth (as has been made evident by ample instances of self-deprecating humour) constantly seeks out an adversary within the limits of Piffling – sometimes even daring to venture beyond – which focuses more on the banal struggles at the heart of that tortured self and imparts a cautionary disclaimer with utmost subtlety: brokenness is a mismeasure of heroism, it leaves a mind incapacitated to be truly cognizant about our own selves, and our doubles, the others. The residents of Piffling aren’t heroes, they utterly lack the incentive to become one. But they are significant because their lack in self-worth can only be ruthlessly teased out – and gently tended to – by the validation they seek (although they might not be ready for it), and eventually find, amongst each-other and not in a renunciation of company. Regular enchantments to the comic irregularities of everyday, Wooden Overcoats is an unapologetically intimate affair with the morbid and the grotesque which gleefully abandons all pretences of order because real life rarely has any. So, sneer all you will, but the spectre of this podcast is going to haunt listeners – and any serious upcoming exercises in the world of audio comedy – for the longest time. Go, funn yourselves!

About the author :

Anuja Dutta

Independent Research Scholar specialising in Literature and the Social Sciences, Kolkata, India