Written By: Amitava Gupta

Kolkata, India

Illustration: Sagar Mondal

Irony died a painful death (hopefully not as painful as being lynched, though) when arguably the most divisive Prime Minister India ever had unveiled the Statue of Unity in Gujarat. The statue is destined to enjoy a short stint of fame being world’s tallest statue, only to be dwarfed by the statue of Shivaji that BJP is building in neighbouring Maharashtra.

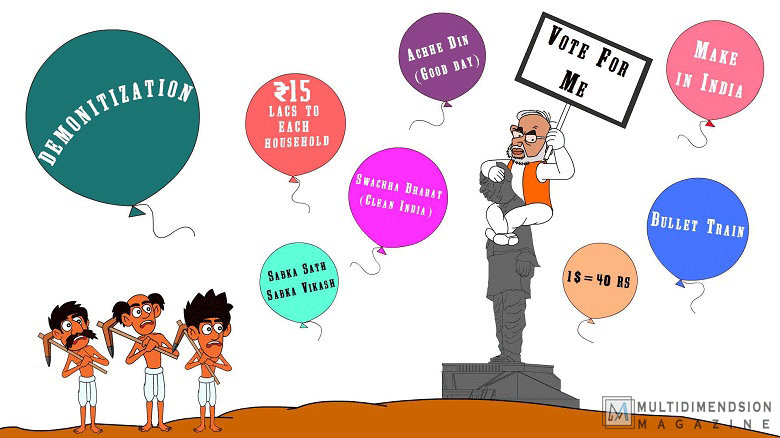

Since Prime Minister Modi unveiled the statue on October 31, India has been on the boil. In all fairness, one should laud the Prime Minister for honouring at least one of his pre-election promises. Though India is still awaiting Achche Din on most counts, the statue is there in full glory. Modi promised to celebrate the astute Gujarati freedom fighter Sardar Ballavbhai Patel, whom he considered to be mostly neglected and sidelined by the Congress. Though among other commemorative measures, Gujarat’s (the state Patel hailed from) most important airport is named after him and one of the major dams in the country bears his name, one may concede that Patel did not get his fair share of laudation from the Congress. However, does that make Modi the heir apparent of his legacy?

Along with Nehru, Patel was the most trusted lieutenant of Gandhi. He was widely acknowledged to be the ‘Ironman of India’, an honorific signifying his unflinching commitment to the statehood of India. When the first independent national cabinet was formed in Delhi, Patel was appointed the Deputy Prime Minister as well as the Home Minister. Until his demise in December 1950, he yielded significant power and authority. Among other decisions he made as the Home Minister, banning the Rashtriya Swayamsevek Sangh (RSS) in the aftermath of Gandhi’s assassination stands out.

What made Modi choose to make a hero out of the person who banned the former’s parental organisation? The question could have been rather perplexing but for the fact that the Hindu rightwing does not have a single ideologue who could even remotely resemble a figure that the nation may unquestionably honour. Sangh’s most celebrated ideologue Vinayak Damodar Savarkar ostensibly had the dubious distinction of writing the maximum number of mercy petitions to the colonial rulers from his confinement in the infamous Cellular Jail in Andaman. Another ideologue, ‘Guruji’ Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar famously championed the ways of the Nazi and was a diehard fan of Adolf Hitler. Other heroes of the Sangh such as Deen Dayal Upadhyay (who recently had an important railway station named after him) hardly makes it the nationalist honour roll. The facts that the RSS stayed steadfastly away from the Quit India movement and apparently worked for the British, or that they did not acknowledge the Tricolour as India’s national flag for a long time are not helping them either.

The only major party in India that had a legitimate claim on Indian nationalism is the Congress. So, when Modi chose to portray their brand of Hindu nationalism as a legitimate nationalist concern, he was in desperate need of nationalist heroes. Besides, he needed heroes who were supposedly wronged by the Gandhi-Nehru duopoly in Congress. Patel was one such choice, but certainly not the only one. Modi tried to usurp Bhagat Singh, the revolutionary martyr from Punjab, who is still revered as a youth icon in the country. Though any self respecting historian would contradict the claim that Bhagat Singh was antagonised by Nehru, BJP constructed such a story around him. Recently Modi tried his hands on another nationalist hero, the Bengali leader Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. His falling out with Gandhi is as well documented in history as his camaraderie with Nehru. Modi, however, chose to ignore the latter. The task is rather a difficult one for him, one must appreciate, for the fact that Bose or Singh or Patel, whatever be their personal equations with Nehru, were all as appalled by the idea of Hindu nationalism of the Sangh as Modi’s bête-noir was. The nationalist history of India has predominantly been critical of the communal manoeuvre of the Sangh.

Modi still clung on to Patel and built the statue. He deemed Patel to be the unifier of India for the fact that he made some 562 princely states (the states which paid taxes to the colonial power but were not directly under the colonial rule) to integrate to the newly formed union of India. This was undoubtedly a remarkable feat, but would hardly be the most significant achievement of Patel. His pivotal role as the backbone of Nehru (a description once put forward by Gandhi) in the nationalist struggle is conveniently ignored by Modi. So is the plight of the 75,000 odd tribals evicted from the site of the statue and left to their destiny. They are yet to receive proper rehabilitation. While the gigantic statue is encircled by a large water body, the tribals are denied irrigation. Patel would have certainly cringed at the idea that protesting tribals had to be arrested in order to keep them from disrupting the unveiling ceremony. He would have preferred to die a thousand deaths before he was honoured by someone whose rule has seen a quantum jump in communal violence in the country. He would have severely rebuked someone who spent a colossal Rs. 2997 crores to build a statue in a country where children die helplessly breathless in hospital beds because the oxygen bill was not paid.

Modi, I suppose, couldn’t have cared less. Make no mistakes; this statue has as much to do with Sardar Patel as Gandhi’s specs has to do with the Swachch Bharat Abhiyan. The statue is of Modi’s arrogance, of the pride he takes in unveiling world’s tallest monument. One would hardly be wrong to see only a man’s megalomania in the theatre of the absurd that unfurled in Gujarat a week ago.

The author is a senior editor based in Kolkata