Written by : Dr. Anup Shekhar Chakraborty

Photo : Shutterstock.com

Vexed Histories

History writing, its interpretation, and conception of any event as history are markedly selective and involve ‘political’ choices and decisions. The methodology infused into the engagement and resource collection and documentation is strongly marked by familiarising and de-familiarising select events. Thereby the event is perceived through what Foucault calls a gaze. In many senses, the gaze of history which fills our knowledge/information for the common is marked by the statist enterprise (governance, governmentality). In short, history is a political engagement in many senses not merely because of the selective choices of what is to be highlighted as historical and what is to be occluded. The pedagogical enterprise is also to be taught, rehearsed, and classified as a memory of the ‘state’ and the ‘public’. What is selected or trained as history to be remembered and forgotten is very much political in intonation. With this understanding at the back of our minds, the paper attempts to glean the multiple versions of histories, claims and counterclaims to territories, experiences of multiple Partitions and memories of the lost past, lost autonomies operative among the Zo Hnahthlak in the state of Mizoram and the overriding versions (‘official’) of the Indian state.

The case of Khuangchera

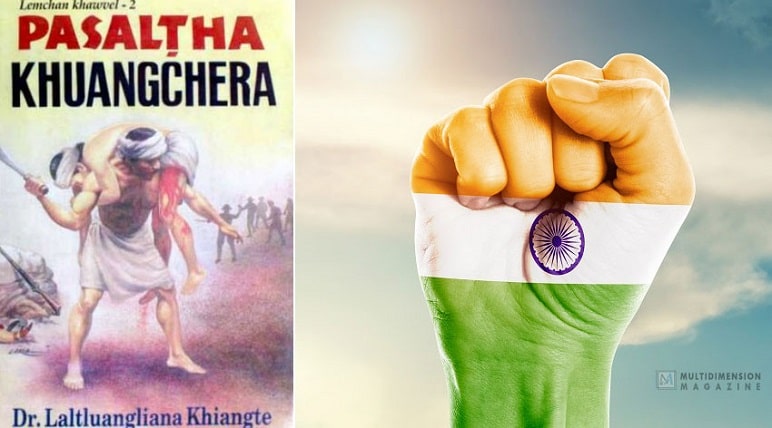

The translation of Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte’s Pasaltha Khuangchera (1997, in Mizo) to Shoorvir Khuangchera by C. Kamlova, an expert in Hindi from Mizoram has generated uncomfortable historical rumblings. The book was declared the ‘Book of the Year’ by the Mizo Academy of Letters and translated to English later. The author was keen to have the book translated into Hindi to increase its readership and share anti-Colonial nationalist discourse narratives. In an interview, the author mentioned that Khuangchera deserves to be in the league of national heroes such as Subhas Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh. He further claimed that Khuangchera deserved to be posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna for his role as an Indian freedom fighter. The author mentioned that Khuangchera was the first Mizo freedom fighter to resist British imperialism in the Lushai Hills (Zo region). The Pasaltha was killed trying to resist advancing British troops in the Chin-Lushai expedition of 1889-90, with a lesser-known Mizo warrior, Ngurbawnga at Changsil near Aizawl. Khuangchera Memorial Committee commemorated the site of Khuangchera’s death with a stone slab.

Here comes the problem that I intend to unweave. Though the author and the Mizo Academy of Letters showed keenness in promoting Khuangchera as a Pan-national hero in India, the Mizo Zirlai Pawl (MZP), the largest students union and the Nexus of Patriarchy were uncomfortable in sharing the Zo national icon with the others (rest of India). The local political parties neatly sided the churches and its nexus and targeted the BJP led Central Government of ‘claiming Khuangchera’. The local apprehension was that in the attempt to write newer histories linking the northeast to the more extensive history of South Asia, the Modi government was crossing the lines of appropriation of local accounts that had their independent narrative sync comprehensive records.

Here we come to the brutal realities of paying respect to freedom fighters and identifying who is to be commemorated as an ‘Icon’. The task of generating a list of nationalist icons becomes more challenging where the idea of ‘India’ or ‘an Indian consciousness’ may or may not have existed. One of the most tedious public relations exercises in this direction is generating a list of nationalist icons. The list as compiled by successive governments at the centre is ever-expanding. But very often, in such situations where such freedom fighters list does not exist, it becomes necessary to manufacture or invent one.

The post-colonial history of resistance in Lushai Hills is highly selective, and records tend to occlude women and sub-tribes’ role. Though, the ‘enemy’ for the larger part of the colonized world was the same as the ‘White/colonial master’ and British Rule, the ‘national heroes or icons’ were definitely different. The Mizo chiefs and their widows were forced to negotiate their existence with the colonial government and often became the fence-sitters, or the other/ the enemy within. During this critical time, many women chiefs, including Ropuiliani, emerged in the colonial archives. Very few women find mention in the official account of the region. For instance, the chieftain Ropuiliani became an ethnic idol of patriotism. Still, other women who struggled against colonialism like Buki, Lalhlupuii, Rothangpuii, Vanhnuaithangi, Laltheri, and Darbilhi Neihpuithangi, Pawibawia Nu, Dari, Thangpuii, Pakuma Rani, Zawlchuaii and others remain comparatively lesser known. In this exercise of naming and faming a local hero to the status of a ‘National one,’ we can see the institutional drive to claim parts (‘selective history’) of the Zo local histories and append it to the grand History of India. The oppositions and the voices in the public sphere in the region can be construed to reflect the ‘resistance histories’ to sync with the institutional one.

(The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Multidimension’s editorial stance.)

About the author :

Dr. Anup Shekhar Chakraborty

Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science and Political Studies, Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, & member, Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata

Visiting Faculty, Department of South and South East Asian Studies, University of Calcutta.

Religion and Politics in Mizoram Hardcover – 1 January 2019

Politics of Autonomy and Ethnic Cocooning in Mizoram Hardcover – 1 January 2015

Politics of Exclusions and Inclusions in India Hardcover – 1 January 2016

Politics of Culture, Identity and Protest in North-East India (2 Volumes) Hardcover – 28