Written by: Amitava Gupta

Kolkata, India

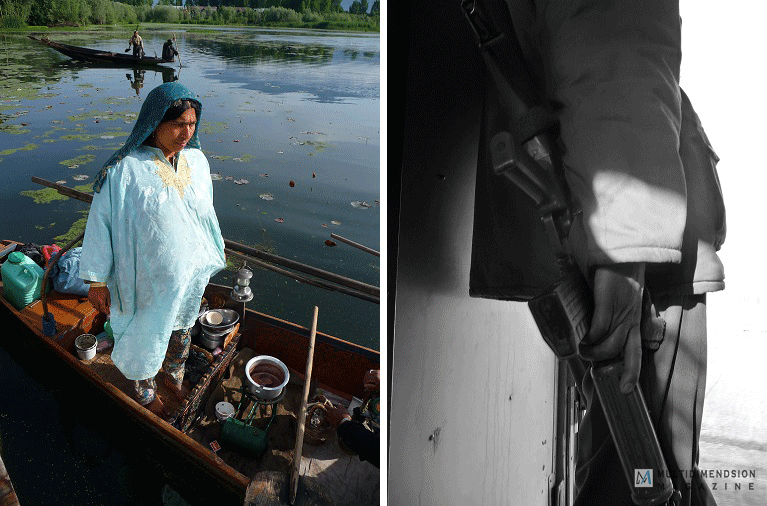

Photo Credit: Lydia Gaudin, Altaf Ahmad Budoo

It does not take much to understand why BJP is against Article 35A in Kashmir, which was added to India’s Constitution through a Presidential order in 1954. This article gives the state legislature of Jammu & Kashmir the discretionary power of defining permanent residents of the state. None other than the permanent residents can acquire immovable property in the state, nor can ‘outsiders’ get government jobs or stake a claim in any government scholarship or other forms of aid. Put simply, Article 35A makes it difficult to change the demographics of the state. The valley is predominantly Muslim and BJP is yet to make much political inroads there.

The 2014 Assembly election in J&K is a good case in point. BJP had the largest vote share among all contesting parties in the state. Its tally was 23% of all votes polled, slightly higher than the PDP (22.7%). However, it managed to gather a measly 2.2% vote share in the Kashmir valley. Among other reasons, the fact that BJP is acknowledged to represent the Hindu interest played a significant role there. Over the last four years, the PDP-BJP alliance was dismantled and the junior partner in the alliance is yet to gain much popularity in the valley. The fact that BJP puts a premium on Kashmir is apparent from getting the RSS veteran Ram Madhav to head the state unit of the party. Altering the population composition of the valley in favor of the non-Muslims may seem to be a shortcut to political dominance in Kashmir. Repealing Article 35A would do that for them.

In 2015, Jammu & Kashmir Study Centre, a RSS-backed NGO, challenged the Article 35A at the Supreme Court claiming that the article was not added to the constitution following proper procedure and it violates Article 14 of the constitution, that is, equality before law. The apex court is scheduled to hear the case on August 27. Though constitutional experts such as A G Noorani, do not see much merit in the petition and hold the article to be constitutionally tenable, the political significance of the petition is beyond doubt. Whether the concerned article stands legal scrutiny or not, this is certainly a step forward toward BJP’s long standing commitment of repealing article 370, which confers a special status to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Make no mistake, the fight against Article 35A is a political battle.

A more fundamental question would be: why does BJP see Kashmir as an imperative political project? The politics of the Hindu nationalist party curiously mirrors the political rhetoric across the western border in which acrimony againstone’s neighbor is always one of the central beliefs. Kashmir has remained that bone of contention which keeps the jingoistic, hyper-nationalist politics alive on both sides and BJP never failed to milk that. In the light of accentuated military repression in the valley in recent years, one may be tempted to argue that BJP took a step forward and construed Kashmiris to be the enemy of the nation. The valley being more than 96% Muslim perhaps helped BJP see them as adversaries. A military as well as a political victory over the Muslim population of the only Muslim-majority state in India is in a way BJP’s proxy victory over Pakistan.

Integration of Kashmir to the rest of India has been their long standing demand. Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the ideological compass of BJP, has held that the special status and a comparative autonomy conferred on J&K through Article 370 is an undue advantage that the state has been privileged with. As it is often the case with the saffron nationalist brigade, they have been twisting and turning history to their advantage in the Kashmir issue, too. If anything, Article 35A, which came to force through Article 370, is the relic of Kashmir’s losing autonomy over its territory.

A nugget of history is in order. Was Kashmir an inevitable part of India when the new nation was carved out during partition? Far from it. The Muslim majority state ruled by a Hindu king was a region of uncertainty was rather compelled by circumstances to join India. In 1947, Maharaja of Kashmir signed the instrument of accession to join the Union of India which gave New Delhi control over Kashmir’s defense, foreign policy and communication. Everything else, including finance, was under the state’s jurisdiction. In fact, the State had its own Constituent Assembly and flag; there were customs checks between India and the State; the Supreme Court did not have jurisdiction over key issues in the State; and Srinagar tried to send its own trade commissioners to foreign countries.

Even the Delhi Agreement between Jawaharlal Nehru and Kashmir’s Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah did not finalize financial integration and required the fundamental rights and citizenship to be granted to the State’s residents via the State Legislature. It took a change in Kashmir’s political power by putting Abdullah in jail and replacing him with Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad as the state premier, and the Presidential order of 1954 for New Delhi to usurp most of the powers that were initially vested with the state. Six and a half decades later, diminutive concessions such as Article 35A remain, which hardly resemble the autonomy that the Union of India promised the valley during accession.

IAS officer Shah Faesal, the poster-boy of Kashmiri emancipation during the Modi regime came out sharply against the move to repeal Article 35A. He was widely quoted in the media as saying that the article is like a marriage deed. Once you repeal it, the marriage is over and there is nothing to discuss anymore. It would be difficult to summarize the debate more succinctly. If BJP’s hyper-nationalism betrays Kashmir again, it will only strengthen the separatists in the valley. Pro-India or pro-peace forces will further lose ground.