Written by : Dr. Anjan Chakrabarti

Photo credit : Shutterstock.com

With our independence, we emerged as a democratic, pluralist, federal, secular, and socialist country, or nation. The 42nd Amendment Act of Constitution added the words socialist and secular in 1976. However, in the last 72 years, the way Indian body polity changed substantially. It implicitly or explicitly contested the concept of India as a nation, India as a secular country, pluralistic nature of Indian society and the very idea of social, economic and political equality embedded in the term socialistic.

India as a nation emerged as an outcome of freedom struggle, it is not a gift of British Colonisers, and they always argued thatIndia as a Nation was a myth, a geographical abstraction consisting of irreconcilable fragments of castes, communities, religions, languages and regions. The British had also claimed that it was only under their rule that a politically united India was established and India was acquainted with political democracy. To clarify the British attitude towards India, John Morley the architect of British Indian policy at the beginning of the 20th century along with the Governor-General and Viceroy Lord Minto, in a talk with a Labour MP said,‘Indian ideas! What are they? Caste, Purdah, Sattee, Child Marriage, female infanticide – these are Indian ideas. Govern India according to Indian ideas – what nonsense.’ The concept of Rastra or Desh (Nation-Country) was an integral part of the cultural and political heritage of Indians. The colonisers had tried their best to destroy the historical memories of cultural unity in India practising policies of racism, discrimination and souring seeds of division among the people of India.

As pointed out in Argumentative Indian by Amartya Sen, ‘the best testimony was provided by the revolt of 1857 in which different section of society, not only challenged foreign rule but also identified the idea of India with the Muslims. “Dilli ruler” Bahadur Shah Jafar, the last Mughal Emperor who was the symbolic rallying point for all those who took part in the struggle, irrespective of their fragmented identities or religion’. The British myth India consisted of fragments of and divided sections of society which had no commonality was proved hollow in the form of anti-partition of Bengal 1905-11 agitation. The whole of Bengal irrespective of religion, caste participated.

When we chant our national anthem,‘…Pônjabô Shindu, Gujorat Môratha Drabiro Utkôlo Bônggo…’ and try to perceive explicitly or implicitly the political geography of British India or psychological unity of United India, not necessarily a nation-state propagated by the West. Or, ‘…hethayaryo, hethayanaryo, hethaydrabiro chin, sakhundolpathan mogul, ekdehehololeen…’

‘The Aryans, the non-Aryans, the Dravida and China’

Sakas, Hunas, Pathans and Mughals

All are merged in one body…’

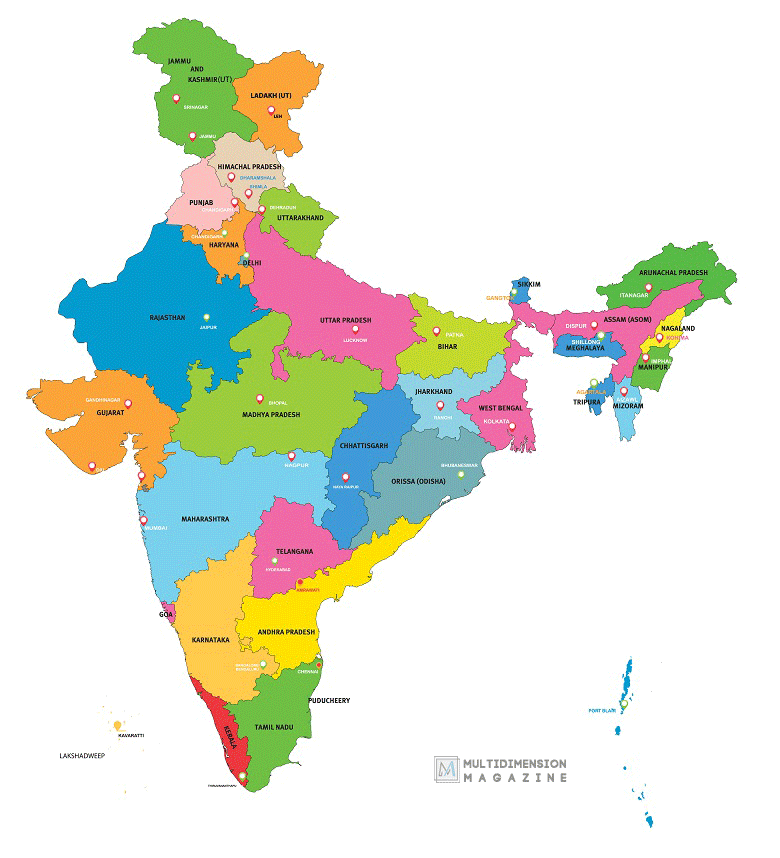

We studied this from childhood, the Rabindranath Tagore’s poem, which reaffirms ‘unity in diversity’ or ‘pluralistic society’ in ideal form.Therefore, it can firmly be said that the concept of Nation and India as Nation, if any, was not the gift of the British, nor an extension of Western ideas. However, the post-independent scenario is a messy one. We got independence with the deep scar of partition, communal riots, and few self-governing territories in parts of North East India and group of princely states with their apprehensions and unwillingness to join in Indian Union. Political Geography of India changed; unity in diversity received a big blow.

Further, in the process of nation-building linguistic reorganisation of India took place, and in 1956 nation India settled the issue of the language-based state by making a diligent compromise with the notion of a pluralistic society. M. S. Golwalkar opposed the idea of the creation of a linguistic state and commented that multiplicity breeds strife, one nation and one culture are my principles. To see oneself as Tamil or Maharashtrian or Bengali was to sap the vitality of a nation and Golwalkar wished them all to use the label ‘Hindu’. The term ‘Hindu’ gradually become a political tool to occupy the political space covertly and overtly.

The Nehru Government considered it advisable to postpone the agenda of the linguistic reorganisation of the country because the Government was confronted by many complex problems, which directly affected the security and national integrity. But, many language groups were impatient, and on 19th October 1952, Patti Sriramalu sacrificed his life over the demand of a separate for Telegu speaking people. It forced the Neheru Government to appoint State Reorganization Commission in August 1953, and the Act was passed in 1956. However, the creation of new states did not stop there. Assam gradually became seven sisters, India’s North-East Region became a conglomeration of seven sisters, and one brother (Sikkim), states have been created on ethnic line. The primary precursor was linguistic and cultural cleavages.Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand were created, and finally, Telegana has also been created. Smaller states are easy to govern, with this pre-text most of the states have been created. Alternative discourse is that smaller states face a hurdle to generate revenues. Secondly, the presence and scope to raise the voice at parliament became marginal and hence less scope to influence the policy-making within the federal structure. These two together made those smaller states more dependent on the Central Government. Therefore, decentralisation within the federal structure is likely to be truncated if smaller states without a robust economic base are created.

Demands for separate states or various kinds of territorial/regional autonomy based on identity, ethnicity, and cultural specificity have been on the rise. In most of the cases, those movements tend to be violent. What is more concerning, some of the states of the North-east region even want to secede from India. Demand for ‘positive discrimination’ keeps on mounting. We see ‘son of the soil policy’ is religiously being followed in Sikkim, in North-Eastern states and a complete entry barrier for non-native Indians in the job-market vis-à-vis labour market with active state sanction. The similar policy has now been followed by many of the Indian states overtly or covertly. ‘India’ as an identity and as a nation has been contested every now and then and possibly, and it will continue to be so.

The response of the state power, in most of the cases, while dealing with the issues of identity or ethnicity, language or cultural-based movements is fraught with ambiguity and plausible solutions, the state generally provide respectively:

i. In most of the cases, the state defines various ethnicity, identity, language or cultural-based movements as an outcome of the nebulous concept of ‘economic backwardness’

ii. State use of coercive forces to muzzle the dissenting voice.

iii. The state often resorts to doling out funds to buy short-term peace with the agitating groups and generally purchase the leadership of the dissenters and as it has been followed for most of the trouble-prone states of North-East.

iv. The state, through negotiation, provides quasi-autonomy without accountability or without grass-root level empowerment.

Implementation of neo-liberal policy since 1991 also has an implicit effect. It is so because the employment opportunities in the government sector are reducing thick and fast over time. Most of these smaller states are non-industrial in nature, and own-revenue generation is abysmally low. Geographical isolation deters the growth of services. Therefore, shrinking job opportunities and siphoning off central funds by a minuscule group of people, abet the frustration of indigenous people. This frustration has been capitalised by the people who prefer to raise the bogey of so-called anti-state movements in the name of ethnicity, culture, and language, autonomy. Less psychological association with mainland India over the centuries helps to fuel the mass sentiments.

Market tries to play a homogenising role because everyone should receive wage according to his or her additional contribution to the production. However, market imperfections, oligopolistic nature of the market and use of capital intensive techniques, either keep the rate of labour absorptions at a low level and low-wage and high productivity has been used to ensure steady profit for the market forces without comprising with the efficiency. It is a common phenomenon of neo-liberal policy. Hire, and fire, no or little provisions for social security have always been practised in an abundant labour country like India since the inception of economic reforms. However, the market economy also increases income inequality across the communities, across the ethnic groups, across the linguistic or cultural groups. The presence or absence of the market may have an implicit or explicit role either to fuel these types of movements, which requires a thorough probe.Therefore, India, as a nation and its political geography, becomes a contentious issue and being contested now and then. ‘Nation’ and ‘Pluralistic Society’ both come under severe challenge and for it difficult to withstand. If we see the political trajectory, then religion, language, caste and sub-caste identity and ethnicity – all become vehicles to occupy political space.

Amartya Sen in ‘Argumentative Indian’ pointed out again that ‘secularism and heterodoxy were part of Indian civilisation’. He referred the Veda and mentioned that ‘the texts of Vedas had laid the foundation for argumentation which is a core principle of democracy and its sustenance. In the Vedas, a basic doubt concerns the very creation of the world: did someone make it? was it a spontaneous emergence? is there a God who knows what happened? As it happens, there are verses in the ‘Rik Veda’ that expresses radical doubt on these issues :

Who knows? Who will here proclaim it? When was it produced? Whence is this creation? Perhaps it formed itself, or maybe it did not. The one who looks down on it, in the highest heaven, only he knows, perhaps he does not know. Let us take ‘Ramayana’. A pundit who gets considerable space in the Ramayana, called Javali, who did not consider Rama as God, Javali calls Rama’s actions ‘foolish’ (for his penchant to harbour suspicious about Sita’s faithfulness). Before he was persuaded to withdraw his allegations, Javali gets time to enough in the Ramayana to explain in detail that there is no afterworld, nor any religious practice for attending that and that the injunctions about the worship of Gods, sacrifice, gifts and penance have been laid down in the Shastras by clever people just to rule over people’. However, ‘Hindu protagonist portrays Ramayana as a document of supernatural veracity. We should not forget that Buddhism was a dominant religion for nearly a thousand years and co-existed with Jains, agnostics and atheists. Indian heterodoxy is remarkably extensive and ubiquitous, and it has direct relevance to the roles of democracy and secularism today’. Had democracy been inculcated by the British, then all the British colonies would have had a democratic form of governance along with India, but it is another way around. It invalidates the claim of our colonisers that they brought democracy in India. ‘This is not to deny that there have been Kings and rulers in India who have not followed Ashoka’s admonition that ‘the sects of other people all deserve reverence for one reason or another’ or Akbar’s insistence that ‘no man should be interfered with on account of religion and anyone is to be allowed to go over to a religion that pleases him’. We do not find similar pronouncements in Europe during that period. As pointed out by Amartya Sen, arguments have two attributes –‘affirmation’ and ‘critique’. The functioning of democracy needs both. However, we are surviving on affirmation in the 21st country in a democratic country called India.

Equality in India also seems to be a flawed project. We did not attack the root causes of prevailing social inequality because problems have been tackled in the wrong manner. The poor, the vulnerable and the deprived population have not been located in the material productive system nor are their social relations linked to it. But the citizens and their rights and levels of deprivations have been identified by their status of birth. The inner logic of prevailing social contradictions and social antagonism has been broken and compartmentalised around fragments like religions, caste, ethnicity-based identities and public policies have been formulated for the alleviation of the living conditions of specific caste groups or religious groups. The political system does not recognise that poor vulnerable deprived is a product of a system whose logic operates irrespective of caste, language, religion, ethnic-based identities. Identity-based approach for fragmented society into caste versus caste, sub-caste versus sub-caste, tribes versus tribes shall lead to social fragmentation at the maximum possible extent and this divisive and socially regressive.

COVID-19 has further exposed the widening economic cleavages that the neo-liberal economy has thrown before us. After seven decades of independence, 70 per cent people are fighting for lives and livelihoods, primary health care and basic needs of life. Therefore, the dreamer of a secular, pluralistic Indian Nation will continue to be interrogated in his or her daily life. In the end, it is a distant reality that India shall ever a become land, where the mind is without fear and where knowledge is free, where the word has not been broken up into fragments by the narrow domestic wall.

(The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Multidimension’s editorial stance.)

|

Dr. Anjan Chakrabarti Associate Professor, UGC-Human Resource Development Centre The University of Burdwan |

|---|